When someone asks me what I do for a living, I usually lie. It’s not that I’m ashamed of what I do. I believe what I do to be a relatively noble thing. I’m not hiding anything nefarious. I’m not a criminal. I’m not a spy. I simply find it too tedious to tell the truth. Besides, there are so many entrenched preconceptions, misconceptions rather, about what I do that to work through and rebut them takes more energy than I can usually muster. I save such discussions for the classroom.

I am a philosopher. That’s what I truly do for a living. I have a PhD in philosophy and have been getting paid teaching philosophy courses for a few decades. I’m retired from my full-time faculty role, but still teach an online course from time to time. I am a retired university professor, but I am not a retired philosopher.

Asking each other about our livelihood is a routine expectation of making small-talk. I’m not objecting to the question being asked. I often ask others this very thing. I suppose most people have never met a professional philosopher. So, when sitting alone on an airplane or in a bar, or mingling among people I don’t know at a gathering, I must gird my loins and prepare myself for the inevitable.

Before I started lying about my livelihood, the small-talk might begin this way:

“What do you do for a living.”

“I’m a philosopher.”

“Oh, I see, you’re a professional bullshitter, ha ha.” Rarely does this person go any further, receiving satisfaction enough from simply insulting me.

Or, I might try to delay and distract, as in:

“You retired recently. Retired from what?”

“I was a university professor.” At this point I’m hoping someone interrupts or the person I’m talking to become otherwise distracted and loses his or her interest in me.

“Oh, interesting. A professor of what?” And we’re back to my conundrum. To lie or not to lie?

Sometimes people just don’t know what to say when they hear the word philosopher. Consider:

“Oh, I took a philosophy course in college once.” I know they’re trying to be nice and relatable, but I can’t help thinking, “That’s nice. I took a course in biology, but that doesn’t make me a surgeon. I took a load of French and German language courses, but that doesn’t make me a linguist. I took a phys ed course. It didn’t make me an athlete. What’s your point?”

Sometimes the word philosopher triggers something like this:

“Well, what is your philosophy?” Philosophers are not gurus.

“So you’re a religious person?” I may or may not be, but that has little to do with philosophy.

I shouldn’t be so hard on people. Most people I talk to associate philosophy with books in some way. They ask whether I write books or what books I find interesting. I’m more comfortable with these sorts of questions. The fact is I like to read books and talk about them. Some of my philosopher friends like to say that this is all philosophy is about. As much truth as there is in that, it’s still a rather vague account of what philosophy is or what I do as a philosopher. Lots of people read books without claiming to be philosophers.

I’ve always liked bookstores. But I found that most of them don’t know how to categorize philosophy. Often the shelves marked philosophy contain self-help books, new age books, books on astrology, and books about religion. None of these things is philosophy. Sometimes bookstores and people in general confuse philosophy with psychology. At least people have some basic grasp of what psychology is. They see people called psychologists on TV. We never see a philosopher on TV (unless it’s a public broadcasting talk show).

My father consistently made this mistake. Visiting my parents during a holiday from grad school I heard my father talking on the phone telling the person on the other end that his son is here for a visit and that he was studying psychology in graduate school. By that time I had been in grad school for a few years and corrected this error countless times. He just couldn’t process it that I was studying philosophy. He wasn’t the only one. More than once people have said to me: “Oh, you’re a philosopher? What do you think of Freud or Jung?”

I was a philosophy major in college. But that doesn’t really allow me to call myself a philosopher in the sense I use that term. It makes me a college student. You have to major in something. I went on the get a master’s degree in philosophy. That doesn’t make me a philosopher either. It makes me a geek. But I continued on to pursue a doctorate (PhD) in philosophy. I think getting this degree allows me to use the label philosopher.

Even though I’ve been teaching philosophy courses to college students, it’s not being a member of the university faculty that makes me a philosopher. It’s the PhD, I think. When in grad school, people, my family, would reasonably ask what I intended to do once I had a PhD in philosophy on my resumé. And I genuinely didn’t know. I never seriously believed that I could secure a rare faculty position at a university. I thought of a doctoral degree as an end in itself. It was a life-long intellectual challenge that engaged me. That would have been enough for me. But I got lucky and secured a life-long faculty position.

So what is a philosopher, then, if not any of the stuff people say at cocktail parties? Perhaps I can explain here what I don’t have the energy to explain at cocktail parties and airplanes. Let’s start by considering what I already said about what philosophy is not. It’s not self-help, new age, astrology, or religion. Philosophy can be about these things, but it is not to be confused with those things. Philosophy is not a doctrine or series of doctrines. Philosophy is an activity. Philosophers do stuff. A reasonable simple definition might be that philosophy is thinking with clarity, precision, and logical rigor. Thinking with clarity, precision, and logical rigor about what? About anything really. But most importantly about our own assumptions and prejudices (prejudices are beliefs without evidence) that we present to ourselves and others as beliefs.

But everyone “thinks.” Everyone has beliefs. Does that make us all philosophers? Not exactly. Not yet. Most people don’t examine their own beliefs. Few people ask the simple questions: Why do I believe this? Where does that belief come from? Most people are even unaware of beliefs they have. Beliefs lead to action. I act a certain way because I believe a certain thing. And since we all act in the world, we all must have beliefs (tacit or otherwise). But the kind of critical reflection that I am calling philosophy involves the clarification of beliefs. What does each of our beliefs really mean? What does a belief commit us to? For a belief to be clear it must be precise. Once we start examining beliefs we often find them to be vague or overly general. In terms of logical rigor we must ask of a belief what does it imply. Is it consistent with or in conflict with other beliefs that we hold? Is it itself supported by other well-founded beliefs? Pursuing this sort of reflection can quickly become quite complex. I suppose that’s why most people don’t do it.

I think most people are content in simply having the beliefs they have and don’t want to rock their own boat by examining them. Sometimes circumstances force us to confront beliefs, to examine or re-examine them, which sometimes leads to what we might call an existential crisis. Reflecting on our beliefs doesn’t always have to be so dramatic. Sometimes we want to improve our lives or some aspect of our lives. We may simply want to regroup and reorder. Perhaps this is why self-help, astrology, and new books are such big sellers. They tend to provide simple analyses and shallow solutions to our problems. This is where astrology, lots of “self-help” advice, and religion come up short. They generally do not not think things through with clarity, precision, and logical rigor.

A simple example. Consider the big three “Abrahamic” religious traditions: Islam, Judaism, and Christianity. Much of the content of each of their doctrines concerns the creation of all things by a God. But those doctrines don’t offer anything by way of an explanation of the very existence of their God the first place. Where does this God come from? Some may attempt to answer this with the simple assertion that our God is eternal, has always existed. But his is just an ad hoc assertion. What could it possibly mean? Is there any thing in the universe that exists eternally? If you say this is a quality only our God has and that’s what makes it God, then you are just going in circles. This is not an example of logical rigor. It is an example of a typical discussion in a college philosophy 101 course.

Or, consider an example from “science.” Someone might try to explain the existence of “everything” by referring to the “Big Bang.” The universe as we know it is the result of a singular explosion billions of years ago. Science may even attempt to put an exact age to the universe by pinning down the moment of its birth, the Big Bang. But what came before this big bang? What existed for it to explode? There must have been something. If so, the theory of the big bang may explain the latest phase in the development of the universe, it in no way explains the origin of all things. Can something come from nothing? That’s another philosophy 101 essay topic.

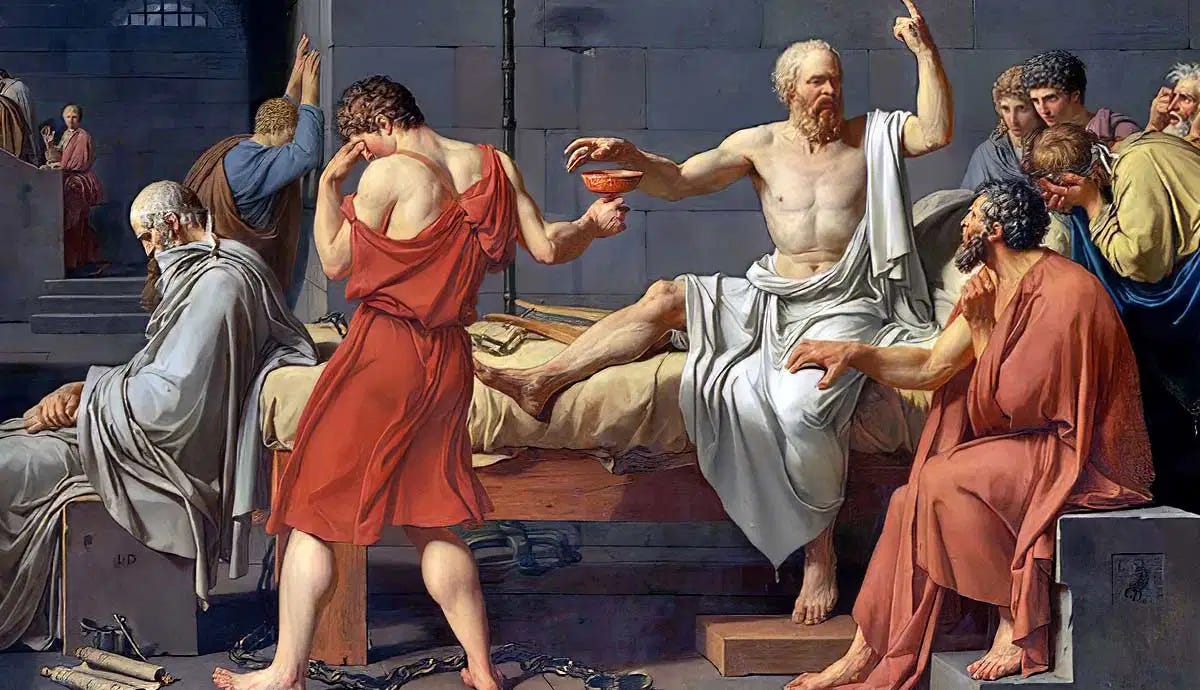

We have many beliefs. Some good. Some bad. Some true. Some false. For a belief to be true it must be supported by evidence. This holds in philosophy as much as it does in science or any other intellectual pursuit. Sometimes evidence comes in the form of factual confirmation. Sometimes it comes in the form of logical coherence. But the bottom line is that a belief is not true because I believe it. A belief is not well-founded because a best-selling author asserts it to be true. Remember, beliefs inform actions. And if our lives are nothing but the sum total of our actions, then having good lives depends on good and true beliefs. This is what Socrates meant when he said something like the unexamined life is not worth living.

Philosophers examine or even criticize people’s views and assertions. At times this can seem pretty impolite, pretty annoying. I think such reactions are based on misunderstandings of philosophers’ attitudes and motives. In the right place and time, such discussions can lead to all participants really learning something. I can learn the strong and weak points of my own and others’ thinking. It is a sign of respect to criticize someone’s beliefs. It wouldn’t make sense to criticize someone’s beliefs if the topic is too trivial to serve criticism, or the person is too immature or feeble to understand what we are saying, or we believe the person to be incorrigible (i.e., unwilling to learn and grow). Criticizing my beliefs says to me you think my beliefs are important and I am rational and capable of learning.

One of the first things discussed in the philosophy 101 course is that the word philosophy is an ancient Greek word. It is a composite of two Greek roots: philein, the Greek word for a kind of love, and sophia, the Greek word for wisdom. So, we have the meaning of philosophy as the love of wisdom. But, of course, the word wisdom itself is fairly vague. Examining beliefs so that we can find good and true beliefs is what I think wisdom amounts to. Is philosophy just bullshit? Is it a typical out-of-touch-ivory-tower pursuit reserved for privileged elites who don’t have to live in the real world? Learning how to examine beliefs in helpful and meaningful ways is about the most practical pursuit I can think of. And helping others to develop this sort of wisdom is far from being frivolous or self-centered. It is, I believe, a noble endeavor.

You can see why I am reluctant to get into all this with the person sitting next to me on an airplane or with a person I just met at a cocktail party. It’s easier just to lie.

2116 words

Thank you for sharing this. I always value the depth of thought and reflection you bring to our conversations. It’s clear this comes from a place of genuine exploration.

Reading this, I felt a strong sense of connection to themes we’ve often discussed—especially about what it means to be human in an increasingly fragmented world. It made me reflect again on how we navigate the balance between finding personal purpose and staying grounded in empathy for others.

Your perspective always brings something new to the table, and this piece is no exception—it’s thought-provoking and layered.

I’m curious, what inspired you to write this? Was there a specific moment or idea that sparked it, or is it something that has been evolving over time? I'd love to hear more about how you approached it.

You have a way of capturing complex ideas and making them resonate. Please keep writing—your work is a gift, and it’s always a privilege to engage with it.